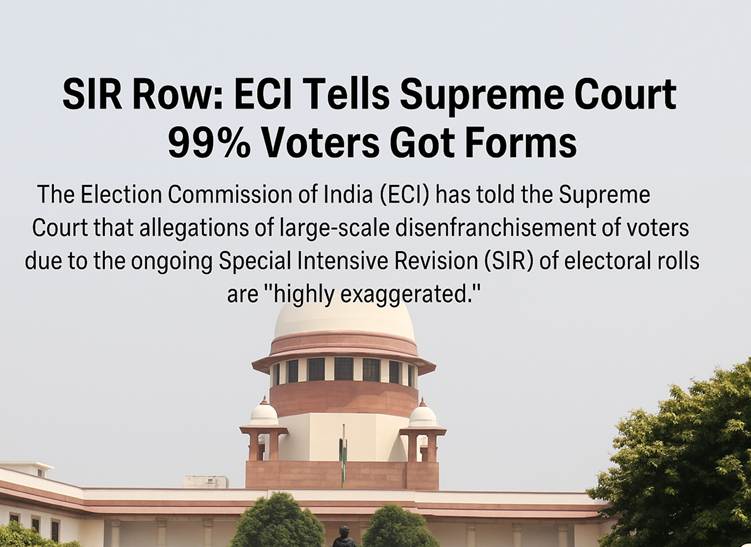

The Election Commission of India (ECI) has strongly refuted allegations that the ongoing Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in West Bengal is being used to disenfranchise voters. In a counter-affidavit submitted to the Supreme Court, the Commission asserted that the accusations are “highly exaggerated” and driven by “vested political interests,” particularly aimed at discrediting a constitutionally mandated electoral cleansing exercise.

The affidavit was filed in response to a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) by Rajya Sabha MP Dola Sen (TMC), challenging the SIR orders issued on 24 June and 27 October 2025.

ECI’s Defence Before Supreme Court: A Constitutionally Mandated Exercise

The Election Commission stated that SIR is neither a novel nor arbitrary procedure. Instead, it is a long-established revision process designed to verify voter eligibility, remove ineligible entries, and update demographic changes such as migration or death.

The affidavit cites T.N. Seshan, CEC v. Union of India (1995)—a landmark Supreme Court judgment affirming that the integrity of electoral rolls is an essential constitutional obligation.

According to the Commission, the narrative portraying SIR as exclusionary deliberately overlooks decades of institutional practice. The sole purpose of SIR, it argues, is to uphold electoral purity, not to “target any demographic or political constituency.”

ECI’s Numbers: 99.77% Voters Served, 70% Forms Returned

The crux of the ECI’s argument lies in its data:

- 99.77% of existing voters have been supplied SIR forms

- 70.14% of filled-in forms have already been collected

These figures, the Commission argues, directly contradict claims of mass exclusion. They demonstrate high compliance and engagement, suggesting that voters are aware of the process and are actively participating.

The ECI asserts that the political narrative of “wide-scale voter deletion” has been amplified by certain actors and sections of the media, without grounding in evidence.

BLO-Level Issues and Internal Cautioning

Even as it defends the revision, the Commission has raised concerns about implementation lapses at the grassroots level. Reports from district administrations indicate reluctance among some Booth Level Officers (BLOs) to mark critical categories such as:

- Absent

- Shifted

- Dead

- Duplicate entries

These non-markings prevent proper categorization and verification. The ECI reminded district magistrates, electoral registration officers, and CEO offices that failure to record such statuses compromises the process and will attract disciplinary action.

This position also signals that the Commission is not ignoring irregularities, but is instead attempting to rectify them.

The Political Climate: Protests, Counter-Protests and Administrative Strain

The SIR exercise has become a flashpoint in West Bengal politics. Demonstrations near the State Chief Electoral Officer’s office in Kolkata saw TMC-associated BLO committees protesting, which quickly escalated into tension when Opposition Leader Suvendu Adhikari visited the premises.

Clashes between BJP and TMC supporters prompted rapid police deployment. Although the situation was normalized, the political message was clear: both sides view the revision exercise as a high-stakes battlefield ahead of upcoming elections.

The Commission has already written to Kolkata police urging enhanced security for its premises and strict enforcement against disturbances. This development highlights the administrative friction between the state government and the central poll body.

Observers Appointed: Tightening Compliance Mechanisms

To ensure neutrality and auditability, the ECI has appointed retired IAS officer Subrata Gupta as State Special Observer for electoral roll revision.

He is supported by 12 serving IAS officers, assigned district-wise to monitor procedural fidelity.

Their mandate includes:

- Reviewing documentation patterns

- Ensuring BLO impartiality

- Auditing form collection and processing

- Recommending immediate corrective measures

The appointment of observers signals that the SIR has moved from being an administrative formality to a high-monitoring operation under national scrutiny.

Why SIR Matters: Integrity vs. Political Messaging

At its core, the SIR exercise is a balancing act between:

Electoral integrity

✔ Eliminating ghost voters

✔ Removing deceased individuals

✔ Updating shifted households

✔ Reducing duplicates

Political mobilization narratives

✘ Claims of systematic voter targeting

✘ Messaging around disenfranchisement

✘ Portrayals of institutional bias

The ECI insists that purifying rolls is not optional, citing constitutional jurisprudence.

Opposition groups argue that execution on the ground is vulnerable to misuse, especially in a politically polarized state.

Implications Ahead: Central Forces and Election Preparedness

As protests and administrative warnings grow, demands for central security deployment are likely to intensify. Opposition figures argue that local police are compromised, while the state government maintains that such demands are politically motivated.

If SIR continues without confidence restoration, West Bengal risks entering the next election cycle under contestation, potentially provoking pre-poll litigation, court supervision, or tighter observer regimes.

The ECI’s submission before the Supreme Court marks a decisive attempt to reclaim institutional credibility amid an increasingly adversarial political environment. By placing hard data on record and acknowledging localized implementation failures, the Commission has shifted the debate from rhetoric to metrics.

Whether the SIR ultimately stabilizes the electoral landscape—or escalates into a broader confrontation between the Election Commission and the West Bengal government—will depend on how transparently enforcement, monitoring, and security are carried out in the coming weeks.